The International Astronomical Union (IAU), the organization tasked since 1919 with bringing order to astronomical chaos, reviews the names proposed for features in the Solar System. Names must follow established themes. On the Moon, craters are mostly named for lunar scientists, physicists, and astronomers. For example, William Herschel, who discovered Uranus and coined the term "asteroid," has a crater, as does his sister and research partner Caroline Herschel, who discovered eight comets. There are craters named for Albert Einstein, Johannes Kepler, Nicolaus Copernicus, Max Planck, Aristarchus, and many other famous scientists.

Living scientists are not commemorated on the Moon. Before a scientist’s name can be applied to a crater, she or he must have been deceased for at least two years. This permits a period of calm reflection, during which the community of scientists can consider whether their colleague deserves a place among the immortals.

In the case of Dr. B. Ray Hawke, who passed away on 24 January 2015, there was no debate about whether a lunar crater should be named for him. B. Ray, as he was known to his many friends, specialized in everything lunar. He was a member of the LROC team and performed lunar remote sensing using Earth-based telescopes. Just as important, he tirelessly mentored lunar scientists as they began and built their careers and dedicated himself to the distribution of lunar data.

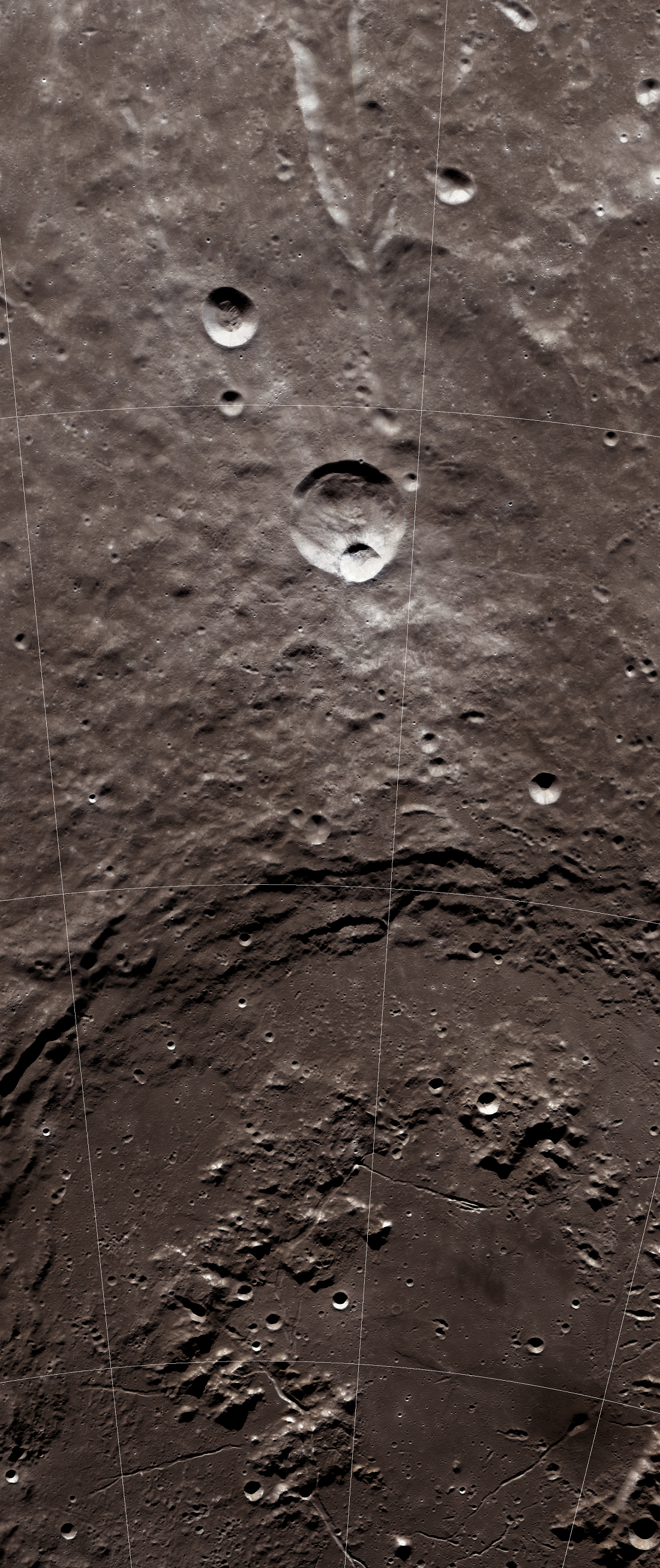

The IAU announced on 16 March 2018 that it had approved the name Hawke for a 13.2-kilometer diameter crater on the lunar farside. Hawke crater, blasted in the rim of Grotrian crater on the ejecta blanket of the vast and ancient Schrödinger basin, displays obvious signs of impact melt and bright rays, lunar features of great interest to Dr. Hawke. Schrödinger basin includes halo craters. These are places where impacts have excavated ancient, buried volcanic deposits known as cryptomare, another subject of B. Ray’s wide-ranging research.

Below you can explore the geologically complex region adjacent to Hawke crater. You can also learn more about B. Ray’s research interests by looking at a sampling of his many papers. Don’t be intimidated by their titles and terminology – that’s the last thing B. Ray would have wanted.

A Sampling of Dr. B. Ray Hawke's Many Lunar Papers

1977: Impact melt on lunar crater rims

1977: Pre-Imbrian history of the Fra Mauro region and Apollo 14 sample provenance

1989: A remote-sensing and geologic investigation of the Crüger region of the Moon

1989: Remote sensing and geologic studies of localized dark mantle deposits on the Moon

1991: Remote sensing studies of the Orientale region of the Moon: A pre-Galileo view

1993: Remote sensing studies of the terrain northwest of the Humorum basin

1999: The composition and origin of selected lunar crater rays

2002: Igneous activity in the southern highlands of the Moon

2003: Distribution and modes of occurrence of lunar anorthosite

2003: Hansteen Alpha: A volcanic construct in the lunar highlands

2004: The origin of lunar crater rays

2005: Remote sensing and geologic studies of the Balmer-Kapteyn region of the Moon

2011: Hansteen Alpha: A silicic volcanic construct on the Moon

2012: The geology and composition of Hansteen Alpha

2015: Cryptomare, lava lakes, and pyroclastic deposits in the Gassendi region of the Moon: Final results

Related Featured Images

Out of the Shadows: Impact Melt Flow at Byrgius A Crater

Forked Impact Melt Flows at Farside Crater

Mons Hansteen: A Window into Lunar Magmatic Processes

New Views of the Gruithuisen Domes

Two-Toned Impact Crater in Balmer Basin

Published by David Portree on 3 May 2018