As the Moon waxes and wanes through its phases, its surface features take on different appearances. When the Moon is bright and full, it appears mottled. Its many shades of gray reveal its surface texture and chemistry.

At the largest scale, the dark maria, or seas, and light highlands appear distinctly different. Maria are made of different kinds of basalt. The ancient highlands are mainly made of anorthosite, the stuff of the ancient global lunar lava ocean and of lunar bedrock. The highlands have been battered and shattered and mixed with debris cast about the lunar surface by billions of years of impacts large and small.

When the Moon shows a phase - that is, when it appears less than full - features along the line between light and dark cast deep shadows, giving them an intricate dimensionality when viewed through a telescope. Mountains, canyons, and the rims and central peaks of craters all stand out.

Some lunar features are best observed when the Moon is full, while others are best seen when the Moon shows a phase. Large, complex Tycho, a crater in the southern highlands of the Moon, is a big crowd pleaser because it looks great any time it is visible.

When the Moon is full, Tycho is a bright spot at the center of an enormous system of brilliant rays. Tycho rays reach 1500 kilometers across the Moon's face, and are easily visible to unaided eyes. They make Tycho one of the few individual craters visible on the Moon without a telescope. Its rays stand out even in commonly available binoculars and inexpensive telescopes.

Because it stands out so plainly to unaided eyes, Tycho, named for 16th-century Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, has been noticed and named many times over the centuries. Pierre Gassendi, a 17th-century astronomer, called it Umbilicus Lunaris, which is Latin for "the Moon's belly button."

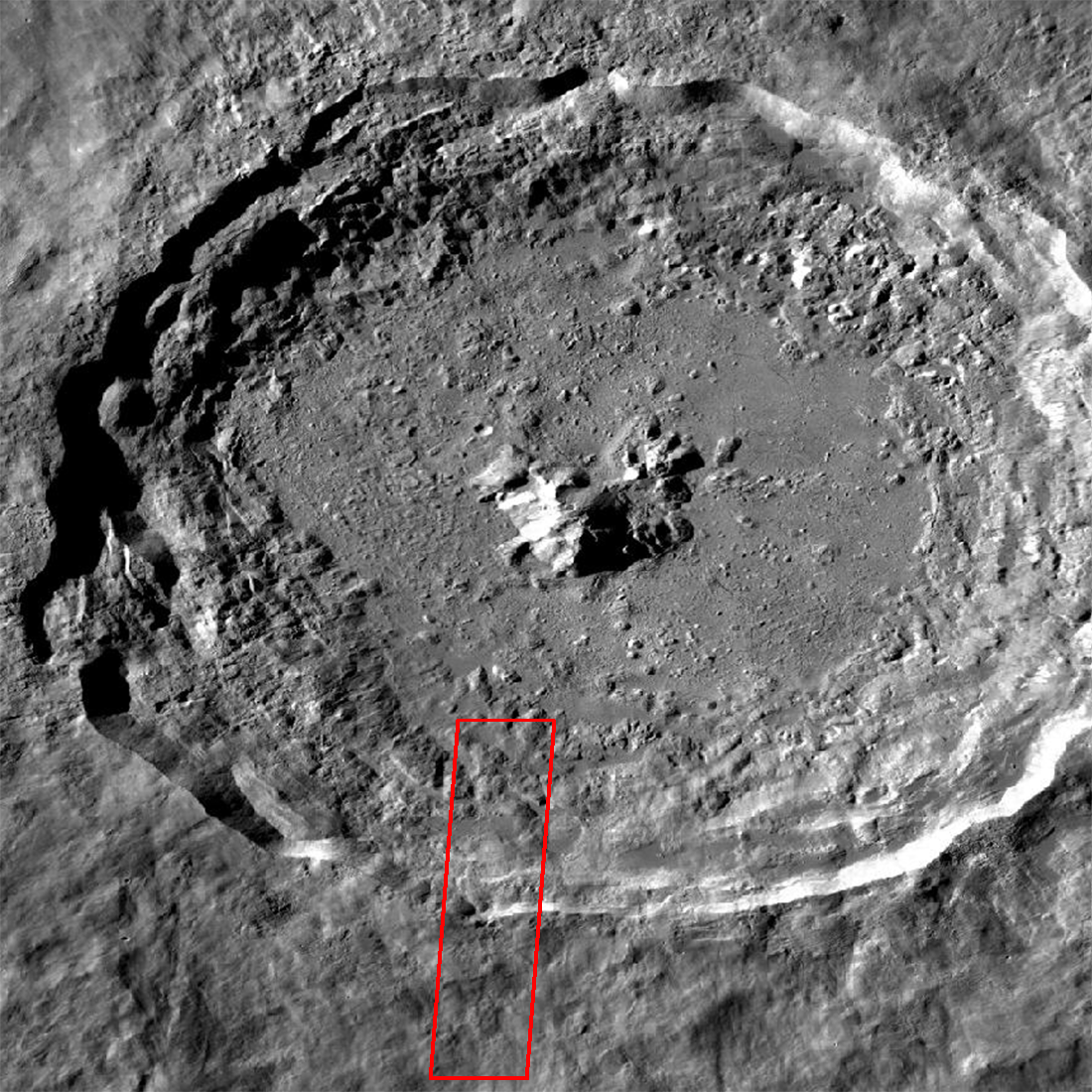

When the Moon shows a phase, Tycho displays the magnificent scale of its central crater. It measures about 4800 meters deep from rim to floor - that's more than twice the depth of the Grand Canyon in Arizona. Measured from sea level and placed on Tycho's floor, Pike's Peak in Colorado would fall half a kilometer short of Tycho's rim, while snowy Mont Blanc in the French Alps would just reach the rim.

When an impact crater forms, enormous pressure compresses and compacts material in its walls. This means that the crater walls often start out steep. Over time, moonquakes and nearby smaller impacts shake the crater, and the wall material loosens up. Then it begins to slump into the crater's interior, gradually forming ledges and terraces. They are like an enormous stairway leading up from Tycho's floor to its rim.

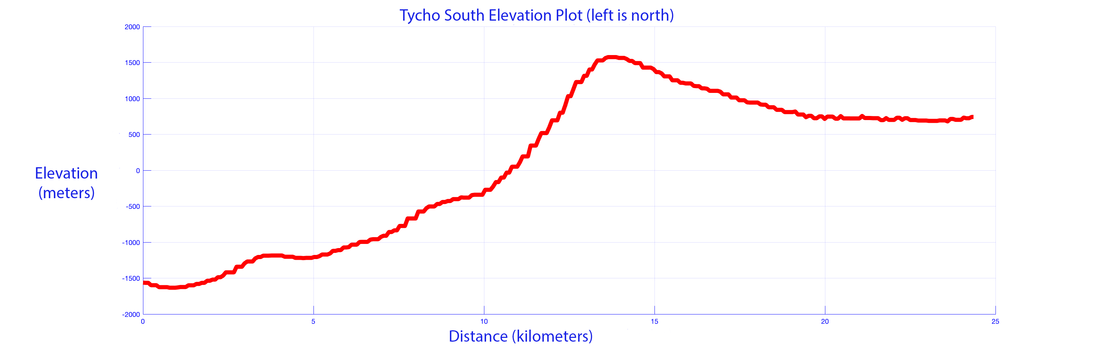

At 108 million years of age, Tycho is near the beginning of a long, slow process of crater degradation. Asteroid and micrometeoroid impacts have not yet worn away all of its sharp edges and melt flows. Its walls have, however, started to collapse and form terraces and ledges. The landscapes of Tycho remain dramatic, however, as graphically demonstrated by the altitude plot below.

Imagine standing at the lowest elevation and looking south, upward toward the rim. Or, better yet, imagine hiking southward and up through nearly impassable terrain under a black sky and glaring Sun, scaling the rim, and then turning to look northward, across the crater.

We will find no shortage of visual wonders when we return to the surface of the Moon.

Related Featured Images:

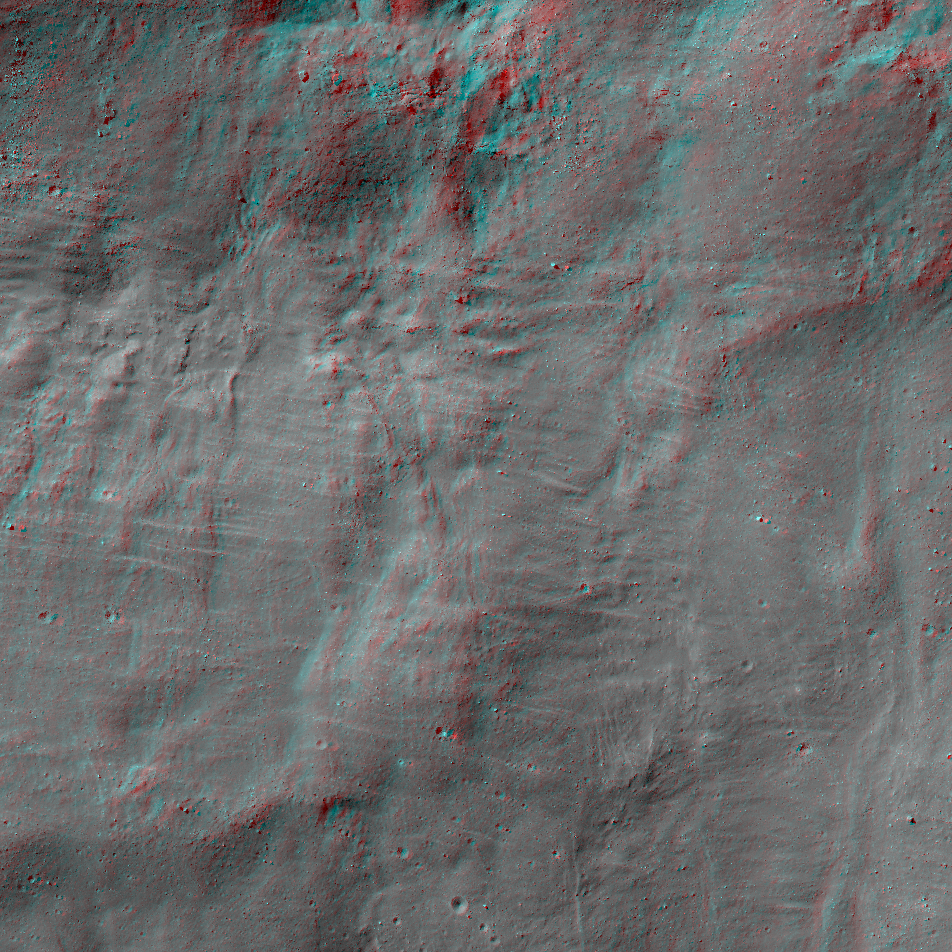

Introducing LROC NAC Anaglyphs!

Mapping Tycho Crater

Chaotic Crater Floor in Tycho

Ejecta in Tycho Crater

Polygonal Fractures on Tycho Ejecta Deposits

Tycho Limb Shot!

Giant Flow of Impact Melt

Shapes of Craters

Published by Kristen Paris on 8 October 2018