The Apollo 16 Lunar Module Orion set down on the lunar surface 40 years ago (21 April 1972) after remaining in a holding pattern for six hours while technical issues with the Command Module Casper were resolved. Here John Young and Charlie Duke undertook the first and only exploration of a highlands site; their main goal was to sample the enigmatic light plains deposits that geologists had interpreted as remnants of a large scale explosive volcanic eruption. These proposed volcanic rocks were to be very different than the volcanic mare basalts sampled at previous sites (Apollo missions 11, 12, and 15).

Once Young and Duke started looking at rocks near Orion, it became clear that there were no strange highland volcanic rocks. What they found were breccias, breccias, and more breccias. Why breccias, and how did they form? The Apollo 16 rocks were most similar to those collected by Apollo 14 astronauts Al Shepard and Ed Mitchell. As it turns out, the breccias formed as part of massive flows of ejecta from the Imbrium and Nectaris basin-forming events. Young and Duke were sampling crushed rocks that flowed hundreds of kilometers from their source!

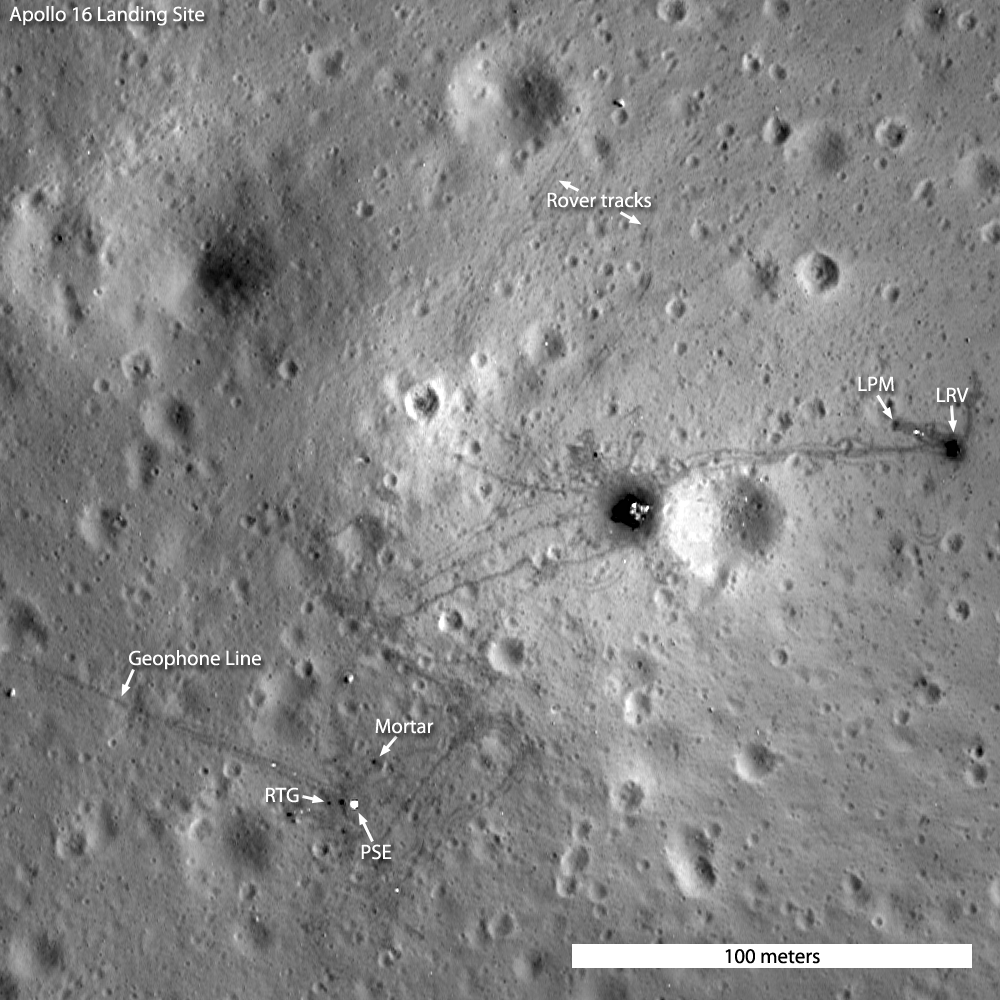

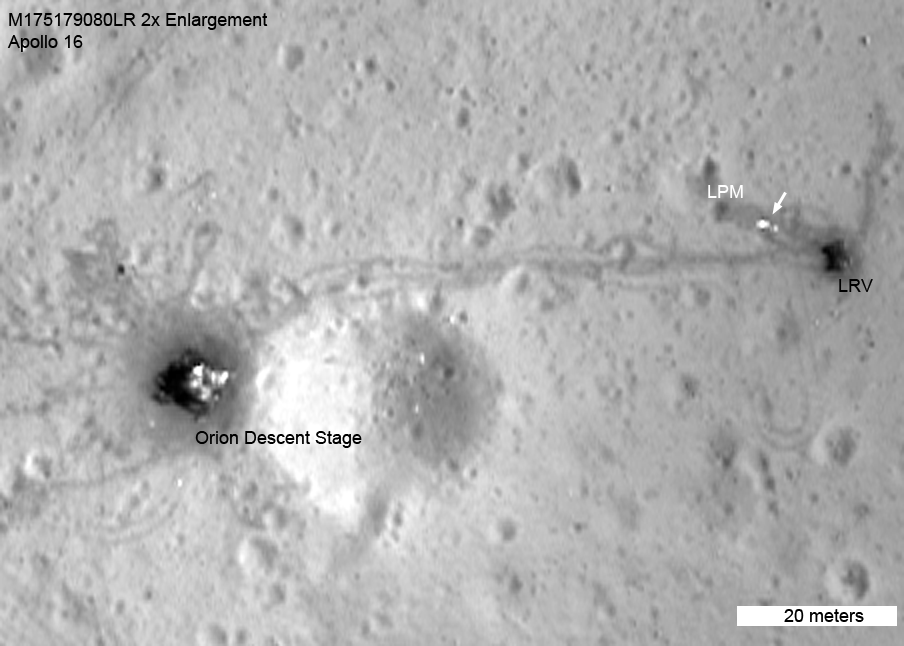

Similar to the other Apollo missions, the Apollo 16 crew set up science instruments to measure varied aspects of the Moon and its environment. Most science instruments were part of the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package, or ALSEP. The Apollo 16 crew also carried with them on their geology traverses the Lunar Portable Magnetometer (LPM) that measured variations in the strength of the Moon's weak magnetic field. Some of the ALSEPs (Apollo missions 12, 15, 16) carried a stationary Lunar Surface Magnetometer (LSM) that provided a point measurement for the landing site as a whole.

The LSMs showed that from site-to-site the magnetic field varied by about a factor of fifty, from a low of 6 gammas (Apollo 15) to a high of 313 gammas (Apollo 16). From the LPM station-to-station measurements within the Apollo 16 traverses, the magnetic low was 121 gammas and high the high was 313 gammas; a factor of nearly three over a distance of 7 km.

After setting up the LPM, a final experiment was performed by measuring the magnetic field before and while a small rock was perched on the experiment. This experiment returned two important results: a) the local rocks had a remnant magnetic field so weak that the LPM could not detect it, and b) that the LPM was still working as before launch. These results came from the fact that the astronauts brought the sample (60335) back to Earth, and it was measured by an identical LPM as well as well as even more sensitive instruments.

What did these varied magnetic readings tell us about the Moon? The Moon's magnetic field comes from crustal and mantle materials, has no dipole signature, and is very weak. This is a magnetic field very different from the dipole field generated in the Earth's core. Right now scientists do not understand the origin of the lunar magnetic field or its variations. Perhaps the signature of an early, but now extinct, dipole field was captured in ancient lunar rocks as they cooled from a magma ocean. Perhaps basin-forming impacts induced local fields in the crust. These Apollo area measurements do tell us that the interior of the Moon is heterogeneous and complicated: the Moon is not a simple body. The two GRAIL spacecraft, Ebb and Flow, that are now in orbit about the Moon will provide gravity measurements that geophysicists will use to deepen our understanding of the lunar interior; the Apollo era magnetic readings will be part of that unfolding story.

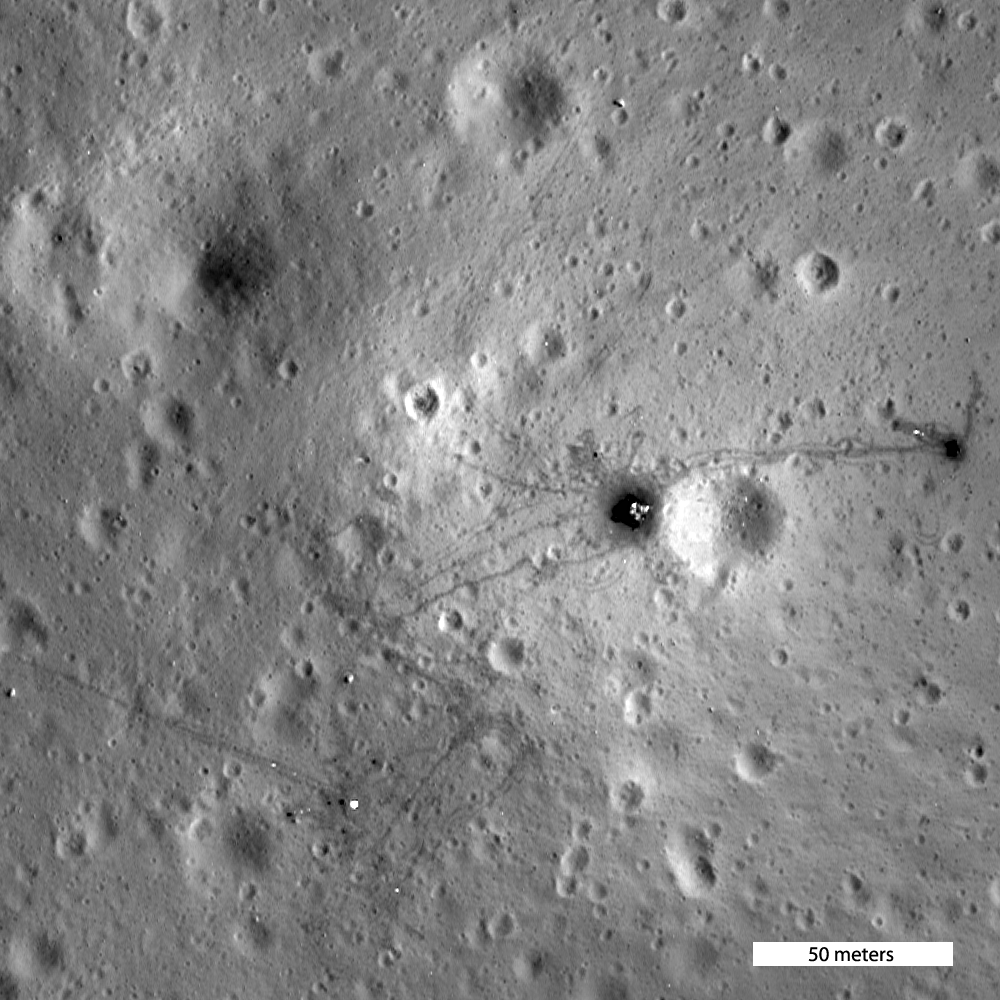

Find the LPM and the rest of the ALSEP hardware in the full NAC image.

Fly over the Apollo 16 landing site and follow the astronauts' journey to North Ray crater and back:

Previous LROC Apollo 16 Featured Images:

Apollo 16, Footsteps Under High Sun

How Young is Young?

Apollo 16 First Look

Previous Low Altitude LROC Image Releases:

Apollo 11

Apollo 12

Apollo 14

Apollo 15

Apollo 16 North Ray crater

Apollo 17

Apollo 17 Shorty crater

Published by Mark Robinson on 23 April 2012