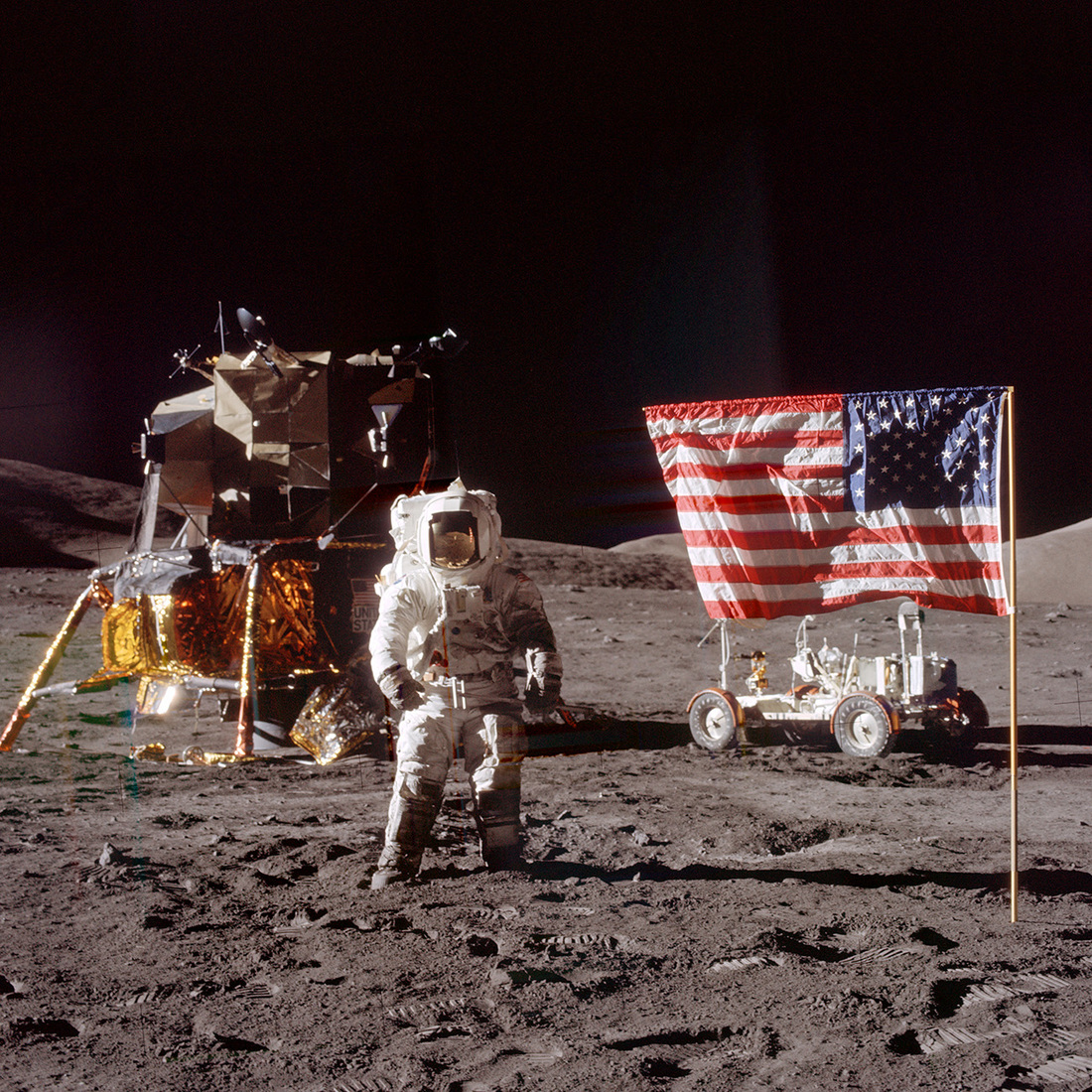

The Apollo 17 crew was the last of an era in human space exploration and the last to set foot on the Moon. Fifty years later, the landing sites, hardware, and footsteps remain delicately preserved on the lunar surface. Join the LROC team as we commemorate their inspiring achievements with additional images, research, maps, interactive sites, and a dedicated video. LROC continues to image the Apollo sites whenever possible, under multiple lighting conditions, and combine these images into interactive sites, like the Apollo 17 Temporal Traverse. The Lunar QuickMap 3D tool can be used to preview the Apollo landing sites and search for LROC images of the areas. For downloadable maps of the Taurus-Littrow Valley, visit the Map Sheets section on our downloads page here. Finally, the Apollo 17 fiftieth anniversary video below presents highlights of the mission with landing site views reconstructed using LROC images and topography.

Journey to the Moon

On 7 December 1972, at 12:33 a.m. EST, astronauts Gene Cernan, Harrison (Jack) Schmitt, and Ronald Evans achieved liftoff beginning the final Apollo mission to the Moon. Cernan, a veteran astronaut now on his third mission, Schmitt, the first and only scientist-astronaut to fly to the Moon, and Evans, the astronaut who would stay in lunar orbit longer than any other human, were starting a journey they knew would mark the end of humankind's first phase of exploration of another world.

The nighttime launch of the mighty Saturn V rocket and crew was the first of its kind. Often reported as one of the most beautiful launches ever, more than 500,000 viewers gathered in the vicinity of Kennedy Space Center (KSC), including the families of the Apollo 17 crew and previous Apollo astronauts Neil Armstrong and Dick Gordon. The rocket turned night to day and was claimed to have been seen as far away as Miami, Florida.

Video of Launch: https://youtu.be/DL8Ql0p2qzo?t=154

After the dramatic launch, Apollo 17 orbited the Earth for a few hours while the crew monitored and checked the spacecraft. At 3:46 a.m. EST, the spacecraft performed a 351-second trans-lunar injection burn, propelling the crew towards the Moon. During the trans-lunar coast, the team captured a breathtaking photograph of Earth from deep space, which would later become one of the most widely distributed NASA images, now known as The Blue Marble. The three astronauts never divulged which one of them captured the photo; instead, they took credit as a team. Later, in jest, each astronaut often individually took credit at commemorative events and interviews. No human since Apollo 17 has been far enough from Earth to photograph an entire hemisphere.

Turning their attention toward the Moon, NASA and the Apollo 17 crew focused on preparing for lunar orbit insertion and executing in-flight experiments. At around 2:47 p.m. EST on 10 December, the Command and Service Module (CSM) engine ignited to slow the spacecraft down as the astronauts approached the Moon. Once a stable lunar orbit was achieved, the crew began preparations for the Taurus–Littrow valley landing.

Touchdown!

The next day, the astronauts performed a series of systems checks and other tasks before Commander Gene Cernan, and Lunar Module Pilot Jack Schmitt transferred from the CSM into the Lunar Module (LM) Challenger. After the twelfth orbit, the two spacecraft undocked and moved into a relatively close distance together in orbit. The LM crew took time to prepare the vehicle for landing before adjusting their orbit and heading toward the surface. Cernan guided the spacecraft towards their target while Schmitt monitored and relayed information from the flight computer. After about an hour of in-flight teamwork, Cernan and Schmitt successfully touched down the Challenger spacecraft on the lunar surface at 2:55 p.m. EST on December 11. "Okay, Houston. The Challenger has landed!" voiced Cernan in celebration. The team had arrived in the Taurus-Littrow Valley approximately 656 feet (200 m) east of the originally planned landing location.

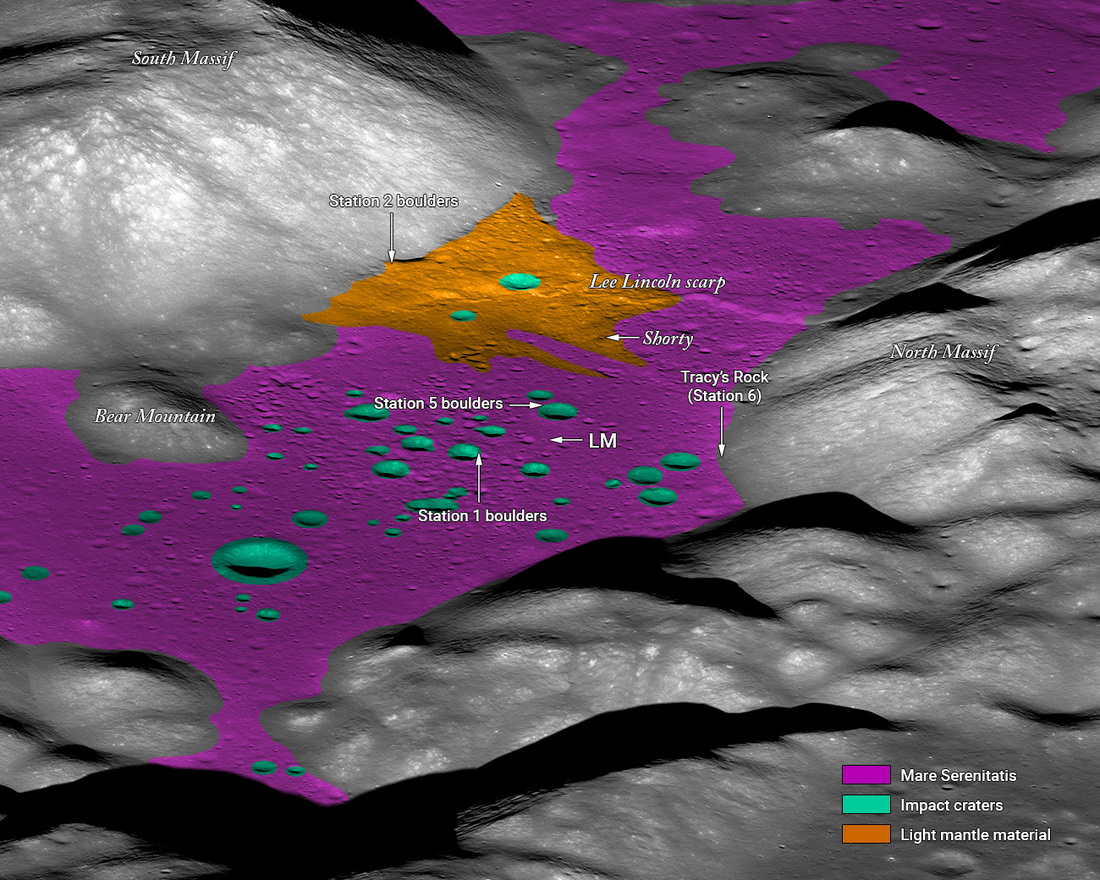

Taurus-Littrow Valley

The Taurus-Littrow Valley, located on the southeast edge of Mare Serenitatis (Sea of Serenity), was selected by NASA for its geologic diversity. This landing site provided access to basaltic lavas exposed by primary and secondary impact craters, pre-Serenitatis crustal material in the North and South massifs, light mantle material that was thought to be an avalanche from South Massif, a huge fault scarp, possible impact ejecta (Tycho crater, Imbrium basin, and Serenitatis basin), and Shorty crater, a depression that geologists thought might be a young volcanic vent.

Time To Explore

The astronauts spent much of the first day setting up hardware and experiments near the LM. The team unpacked and set up the lunar rover, a vital transport for the crew, their hardware, and any samples they would collect across the ~5-mile wide (~8-kilometer) valley over the next few days. Then they set up the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), which included a gravimeter, a mass-spectrometer, a seismic-detection device that utilized geophones, and an instrument to detect the movement of dust particles near the surface.

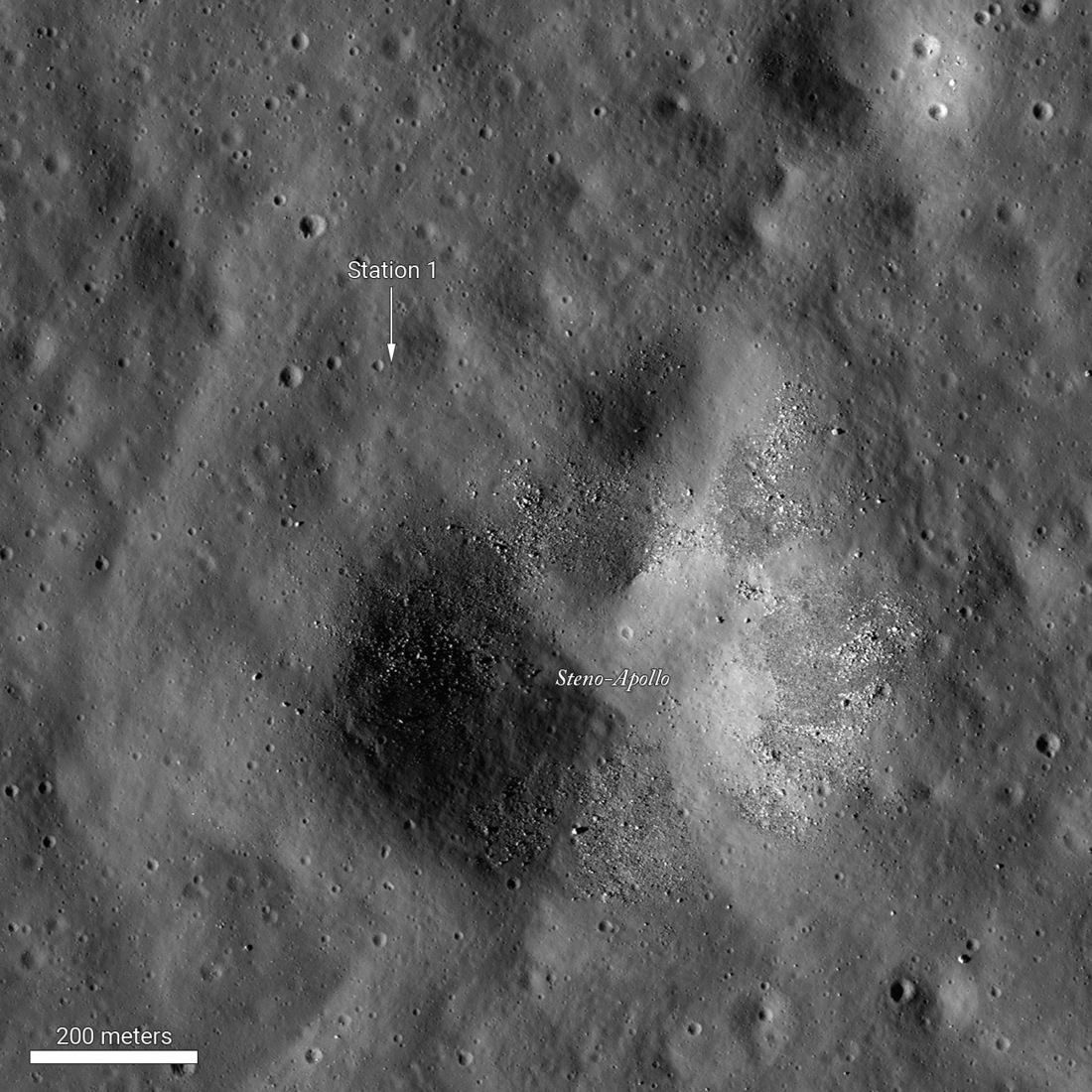

After setting up the equipment near the LM (~4.41 hours), Schmitt joined Cernan in the rover. They drove south-southeast to Steno-Apollo (referred to simply as Steno) crater. The astronauts collected 14 kilograms (31 pounds) of samples excavated during the Steno impact event and deployed two explosive charges. Eight charges would be deployed during the three EVAs at distances up to ~2.2 miles (~3.5 k) from the LM. These charges were detonated remotely after the astronauts departed, and the ALSEP seismometer recorded the shock waves transmitted through the regolith. After approximately 32 minutes at Steno, Cernan and Schmitt drove back to the LM, deployed the Surface Electrical Properties (SEP) experiment, completed a series of EVA close-out tasks, and climbed back into the pressurized LM for some rest.

Orange You Glad To See Me?

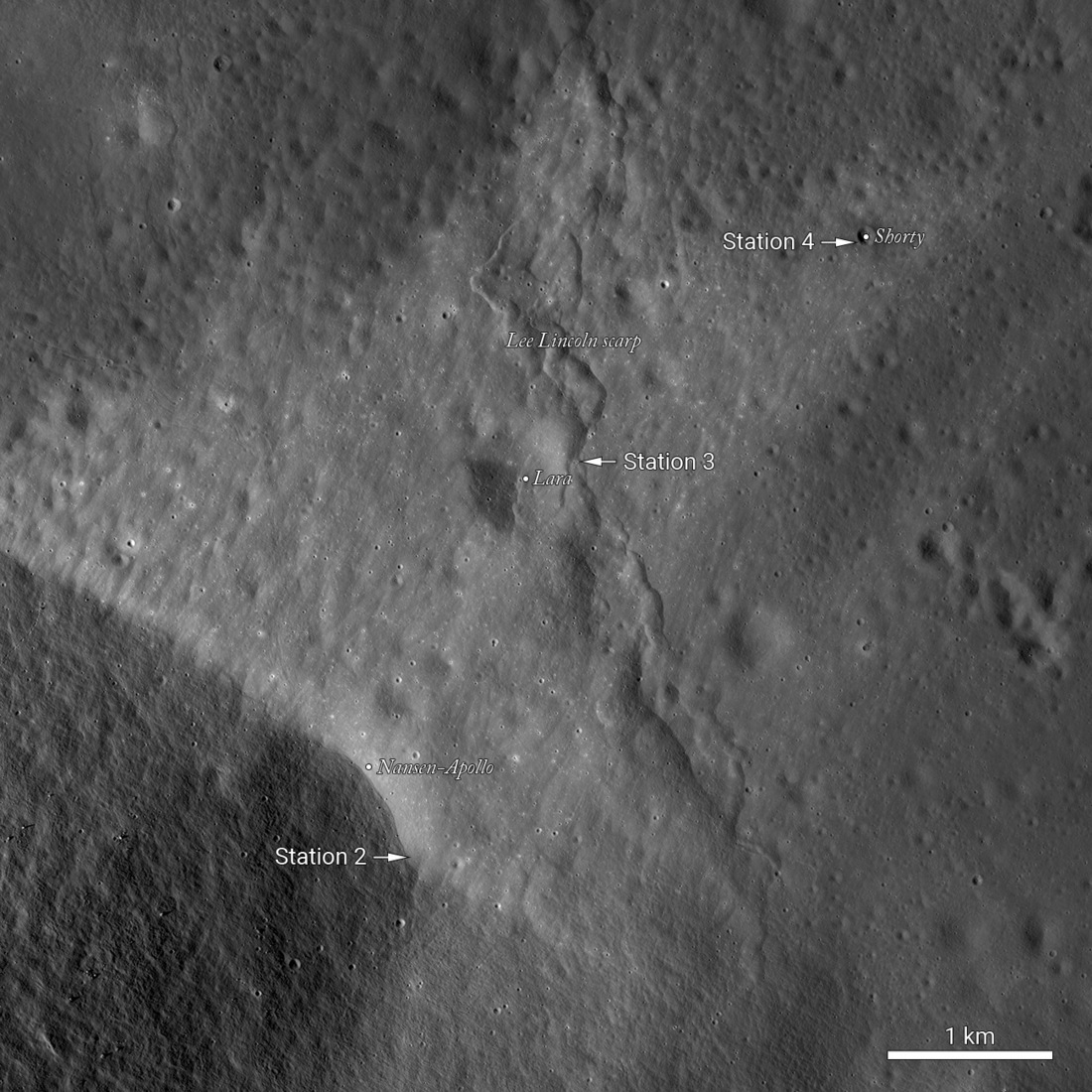

The next day, the astronauts stirred to the orchestral sounds of Ride of the Valkyries, a humorous dedication from Houston to Caltech alumnus Jack Schmitt. The team knew it would be a long day, but Schmitt was particularly excited about what they might discover. The team loaded into the rover and set out on the longest EVA of any Apollo mission. Cernan sped them west to Camelot crater, then southwest to the foot of South Massif and up onto light mantle material ~4.7 miles (~7.6 kilometers), the furthest astronauts would ever get from the safety of the pressurized LM. While at Station 2, the crew marveled at Nansen (Nansen-Apollo) crater and collected more boulder and rake samples. They moved on to Station 3, where Schmitt collected a core sample that NASA maintained in a vacuum for the past fifty years and opened earlier this year!

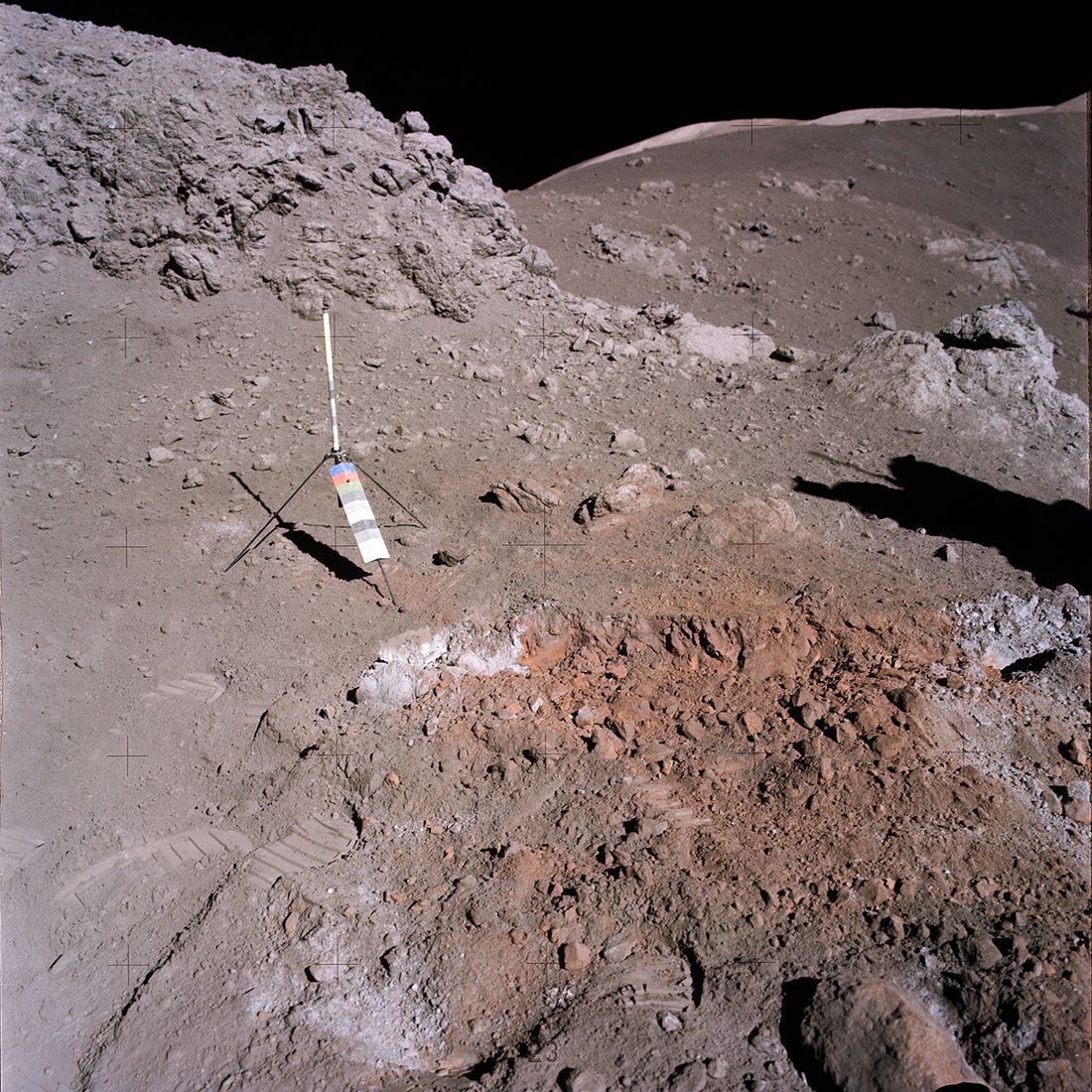

At Station 4, Schmitt immediately identified Shorty, not as the hoped-for vent, but as a dark-rimmed impact crater. The absence of a vent didn't seem to bother Schmitt. In fact, Houston could tell the geologist was in his element and excited as ever. The team continued exploring, sampling, and recording until Schmitt stirred up something that caught both astronauts by surprise. "There is orange soil!" cried Schmitt. "It's all over!! Orange!!!" A large section of orange soil was exposed on the rim of Shorty crater, and the team knew they had stumbled upon something amazing. This soil was composed of small beads of volcanic glass that lined the rim of Shorty crater. Finally, they uncovered evidence of young lunar volcanism. Or had they? The orange (and accompanying black beads ) were volcanic but not young. These intriguing samples were older than 3.5 billion years. The orange and black beads were some of the most significant samples returned by the Apollo 17 crew, the first sampled pyroclastic unit (explosive volcanism) from the Moon. They were created as gases exsolved from a volatile-enriched magma that traveled up from the deep mantle. These samples tell scientists much about the bulk composition of the Moon and, thus, how the Moon formed.

Finally, Cernan drove the rover east to Camelot crater, where they collected more samples, obtained more gravimeter readings, deployed more explosive packages, and took more images. Exhausted and filthy from the day's activities, the astronauts still wished they could have continued exploring, but water and oxygen were running low. The team headed back to the landing site, closed out the EVA, and climbed back into the LM for some rest.

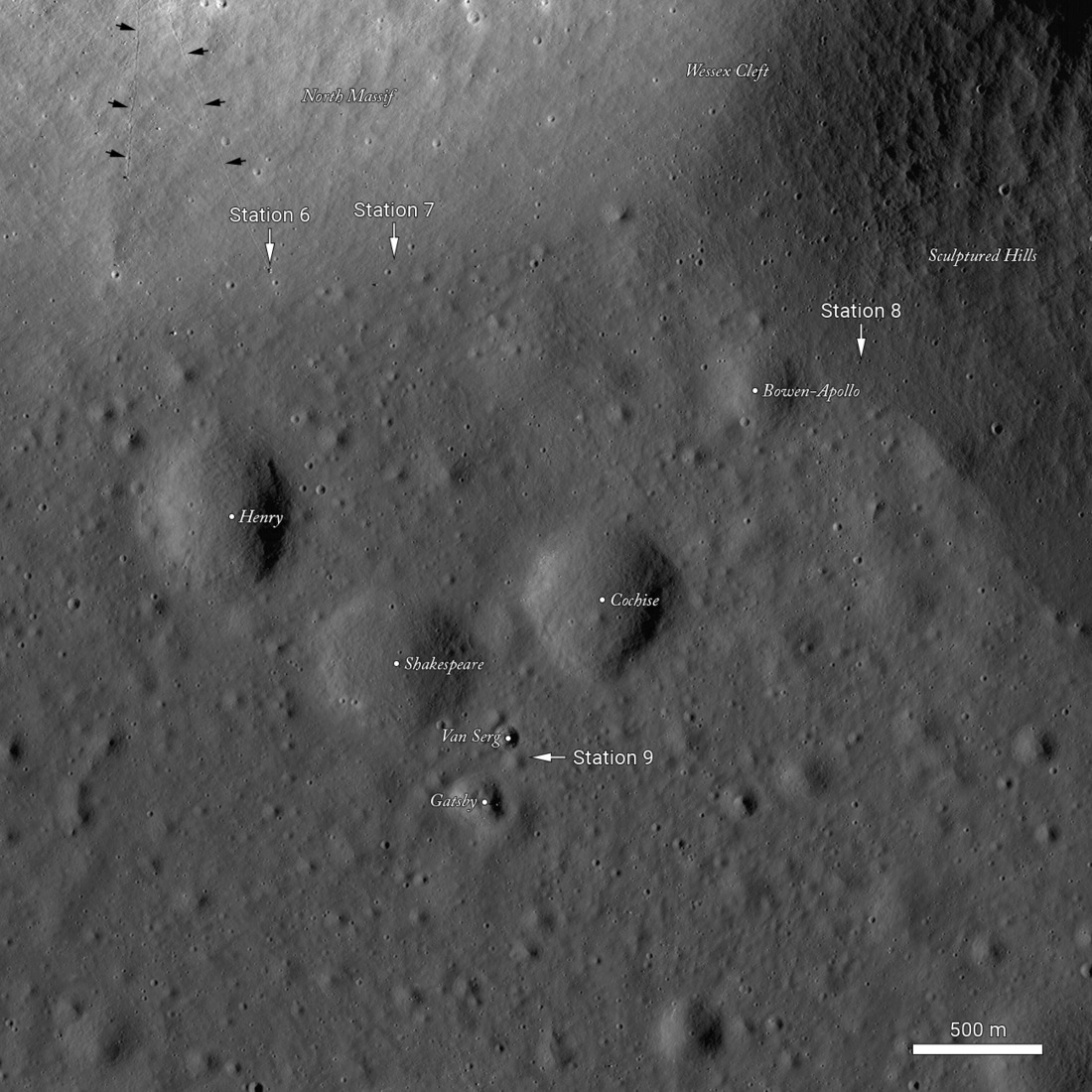

To the Hills

On the third EVA, they headed north to the base of North Massif and east to the Sculptured Hills. At Station 6, the team examined and sampled a house-size, split boulder called Tracy's Rock. The team then drove to Van Serg crater, collected 66 kg (or 146 lbs) of samples, and took nine more gravity measurements. Schmitt noticed an unusual rock that they collected. This rock was the largest Apollo sample collected at 8.0 kg (17.7 lbs) and is the oldest rock collected during the Apollo missions, which was not damaged by impacts or other significant geological events. The team would go on to visit and sample three more stations along the northern slopes, and the samples collected during EVA 3 would help determine the absolute age date for the formation of the Serenitatis basin (~800 kilometers diameter).

One for the Moon

After returning to the LM, Cernan, and Schmitt closed out the last EVA, packed as much as possible, including the rest of their 110.4 kilograms (243 pounds) of samples. While reviewing the packing list, Cernan mentioned to Schmitt that Houston instructed them to leave the rock hammer. About to throw the hammer, Schmitt quickly pleaded for the pleasure of throwing the team's only hammer, which Cernan relinquished happily. "You deserve it. A hammer thrower," said Cernan. "You're a geologist. You ought to be able to throw it." Taking the hammer in hand, Schmitt wound up and threw it high and far in the lunar gravity. Taking images of the event, Cernan commented on the amazing distance of the throw.

Cernan then drove the rover east and parked it facing west so the video camera could capture their liftoff. The rover had been recording their distance, and the team had logged more than 36 kilometers. The team finished their tasks and climbed back into the LM to rest.

The Liftoff

After waking up in good spirits, Cernan and Schmitt finalized their preparations and got ready to depart the lunar surface and join back up with their partner in orbit. At this point, Evans had spent more than three days alone in the CSM orbiting the Moon. He would eventually stay in lunar orbit for more than 147 hours across 75 lunar orbits, longer than any human to date. There were no easy seats to the Moon. Houston kept Evans busy taking scientific measurements and observations from orbit. Evans would eventually get into a groove providing live narration of his days to Houston, much like Cernan and Schmitt had done these past three days approximately 60 miles below, on the surface.

Now, ready to begin the journey home, Cernan and Schmitt coordinated their efforts before liftoff with Houston, who was recording the event from the rover.

Challenger sped away from the surface, and the trio met back up in lunar orbit, reuniting the two spacecraft and heading back home along the trans-Earth coast. The astronauts would splash down in the South Pacific Ocean on 19 December 1972 with a final mission elapsed time of 301 hours, 51 minutes, and 59 seconds. The days of Apollo Moon landings had come to an end. Nobody imagined that half of a century later, the tracks of the Apollo astronauts would still be the last. With the successful launch of the new NASA Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and the recent Orion spacecraft flyby of the Moon, it seems a return to the Moon is finally just around the corner!

More Apollo 17 information, images, and downloads:

Interactive 3D views of the Apollo 17 landing site and the Moon (Lunar QuickMap 3D)

Topography of the Taurus-Littrow Valley (includes Apollo 17 Map downloads)

Approach to Taurus Littrow Valley (includes LROC NAC oblique image download)

Exploring the Apollo 17 Site (further information about the Apollo 17 landing site)

Just Another Crater? (more information and images on Shorty crater)

Bouncing, Bounding Boulders! (further reading and images covering the massif's boulders)

Station 6 - Apollo 17 (further information about Station 6 boulders)

Snapshots From Space (Apollo 17 40th Anniversary post in 2013 from LROC)

Taurus Littrow Valley, West-To-East (includes a west-to-east zoomable NAC oblique image)

Published by Rick Hoppe on 10 December 2022