When you think of the Moon, your first thought probably isn’t about the types of tectonic landforms you might find there. Tectonic landforms are those formed by forces that act to either contract or pull apart crustal materials. These forces develop faults or breaks in the crustal materials, and movement or slip along the faults form either positive or negative relief landforms. On the Moon, positive relief contractional landforms are the most common. The most significant contractional landforms on the Moon are wrinkle ridges, found exclusively in the dark mare basalts (check out the mapped locations of all wrinkle ridges on Quickmap). Wrinkle ridges are also the most complex, typically consisting of a broad, low relief arch-like feature and a superimposed narrow, higher relief ridge. It’s the ridge component that gives wrinkle ridges their crinkly appearance.

Beneath the wrinkle ridge, controlling the size of the ridge and arch is a thrust fault. Thrust faults are contractional faults that displace or move crustal material up and over adjacent crust. The thrust faults cut through the multiple layers of lava flows that make up the dark mare of the Moon. All thrust faults are not the same – they may have a planar geometry that dips downward at a constant angle, or they can be curved, with a steeper angle near the surface that flattens out with depth. The depth the fault reaches in the crust may also be very different, particularly between a planar fault that can be deeply rooted in the crust and a curved or listric fault that is more often shallowly rooted.

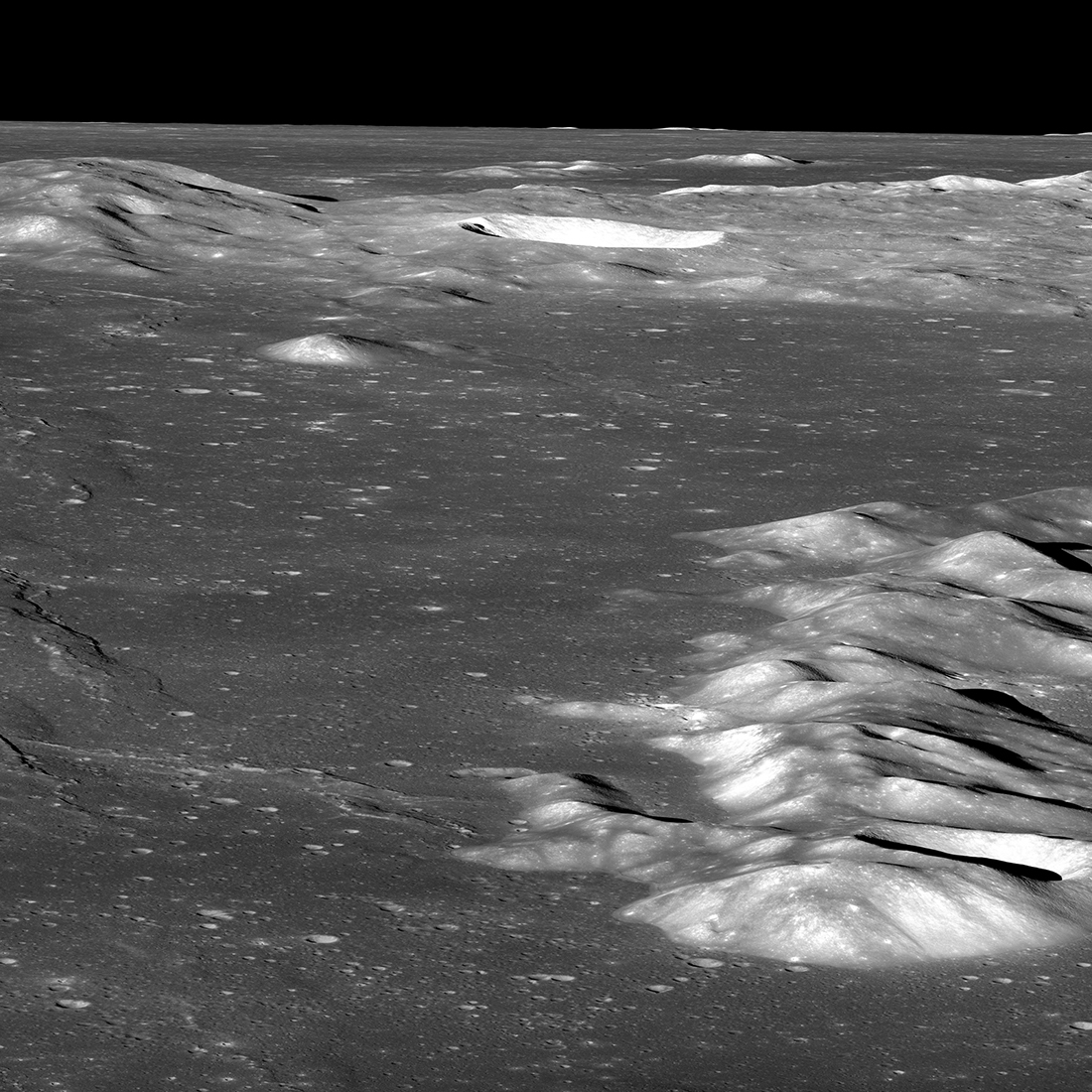

So, how can we tell what type of thrust fault is responsible for wrinkle ridges? One approach is to model both types of thrust faults – planar and listric – and evaluate which one best approximates the shape and size of typical wrinkle ridges. The LROC team has done this, and model results suggest wrinkle ridges are best approximated by listric thrust faults. It also suggests the depth of faulting is relatively shallow. In fact, it’s possible the faults do not reach much deeper than the thickness of the mare basalts they cut through. The predicted shallow depth can be tested using LROC WAC and NAC images to examine wrinkle ridges extending to isolated highland massifs, those completely embayed by mare basalts – exactly the setting in the image above. Here, the western fork of a bifurcated wrinkle ridge meets the highlands massifs of Montes Recti, near the northern rim of Mare Imbrium. LROC images show no evidence that a deep wrinkle ridge thrust fault cuts across and offsets the massif.

In rare cases, wrinkle ridges can transition into thrust fault scarps in adjacent highlands, but these lobate scarps are small, and their faults are very shallow. A wrinkle ridge–lobate scarp transition is also found in Montes Recti where the eastern fork of the same wrinkle ridge meets the edge of the massif. The wrinkle ridge becomes a scarp just above the contact between the mare basalts and the highlands massif, paralleling the contact over a distance of more than 10 km.

Read more about wrinkle ridges and what they can tell us about the Moon's crust in a newly published paper from the LROC team:

Watters, T.R. (2022) Lunar wrinkle ridges and the evolution of the nearside lithosphere, Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 127, e2021JE007058, doi: 10.1029/2021JE007058.

Related Featured Images:

Stress and Pull

Wrinkles in Mare Frigoris

Really Wrinkled

Wrinkle Ridges in Mare Crisium

Wrinkle Ridges of Northwest Mare Imbrium

Wrinkled, But How Old?

Explore or download the full-resolution NAC oblique view of Montes Recti and its neighboring wrinkle ridges below.

Published by Brett Denevi on 28 September 2022