How does one train astronauts on Earth to do field geology on the Moon? You take them to places on Earth that might resemble the places they plan to visit on the Moon — for example, to the shores of Lake Superior, where the ancient Sudbury impact structure is located, or to central Iceland, with its stark young volcanic landscapes. Or, you might bring the Moon to Earth.

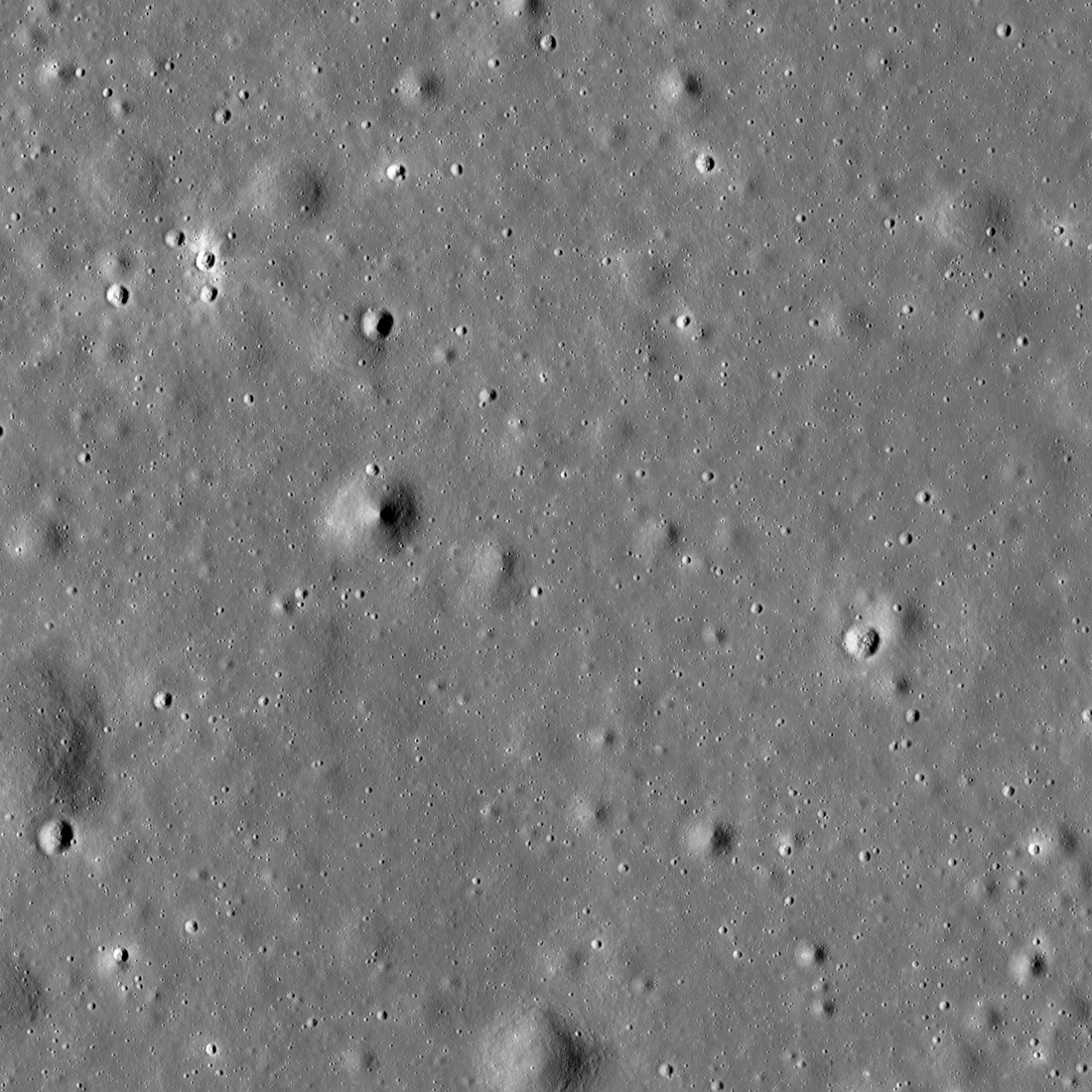

In 1967, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Flagstaff, Arizona, made a 1:1-scale copy of part of the Sea of Tranquility. The near-equatorial area the USGS scientists chose to copy, centered at 0.738°N latitude, 23.675°E longitude, had been photographed by the automated Lunar Orbiter II spacecraft in November 1966. It was near the center of proposed Apollo landing zone called II-P-6, which was high on the list of candidate targets for the first Apollo Moon landing. In fact, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin piloted the Lunar Module Eagle to a landing within II-P-6 about 6.4 kilometers southwest of the area the USGS duplicated. II-P-6 is mostly flat but is peppered with thousands of small impact craters.

USGS geologists made lunar-like small craters by burying and setting off explosives in the Cinder Lakes, located northeast of Flagstaff, Arizona. As you might guess, the Cinder Lakes are not filled with water — they are cinder fields laid down by the Sunset Crater volcanic eruption nearly 1000 years ago. The geologists studied the stratigraphy of the cinder field, then calculated the size of the explosive charges necessary to excavate craters of different sizes.

Cinder Lakes Crater Field 1 includes 143 craters ranging in size from two to 10 meters across. The first section, a square measuring about 160 meters on a side, was completed on 31 July 1967. The second section of Cinder Lakes Crater Field 1, a 260-meter-wide square that encompassed the first section, was completed on 12 October 1967.

In addition to astronaut training, Cinder Lakes Crater Field 1 was used for testing proposed advanced lunar exploration equipment — hand tools, space suits, and rovers — and for conducting simulated Moonwalks to determine the amount of time NASA should budget for astronauts to carry out activities while wearing bulky space suits on the Moon. It was a busy place until November 1972, the month before Apollo 17, the last astronaut visit to the Moon.

USGS geologists made several other crater fields. For example, they blasted out the 354 craters of Cinder Lakes Crater Field 2 in three waves in July 1968. The 282 first-wave craters would represent the oldest small craters on the Sea of Tranquility; they could potentially be partially covered by ejecta from explosions in both the second and third waves, so would appear degraded. The second wave included 61 "medium-age" craters, and the third wave, 11 "young" craters. The USGS recorded construction of Crater Field 2 using film cameras, and turned some of that film footage into a 12-minute video.

The Cinder Lakes Crater Fields still exist today, but more than 50 years of weather and human activity have degraded them. Cinder Lakes Crater Field 2 is now within a recreational area for off-road vehicle enthusiasts, so is barely recognizable. Crater Field 1 is in better shape; in 2006, in fact, the USGS cut back brush and trees on a small part of Crater Field 1 to enable NASA engineers to experiment there with space suits and equipment. Every few years someone proposes a project to restore Crater Field 1 as an historical site for tourists to visit. Unfortunately, construction of a road for public access would be costly, and explosions to remake the craters might damage nearby structures built since the 1960s.

Zoom in on the Zoomify image below to explore the II-P-6 Apollo landing area. A white square at the edge of the image encompasses the area USGS geologists reproduced to make Cinder Lakes Crater Field 1.

Related Featured Images:

A Stark Beauty All Its Own

Just Another Crater?

Americas from the Moon

Each Crater Tells a Story

Published by David Portree on 2 July 2019